Women Witnesses: Proof of an Empty Tomb?

Taking a peek at a popular apologetic trope

You may be familiar with a popular argument for the historicity of the empty tomb.

It goes something like this:

The Gospel writers would not have invented women as the preachers of the empty tomb because their testimony was unacceptable in first-century society. It is therefore likely that Jesus’ tomb truly was found empty on Easter Sunday.

Often, such negative attitudes towards women’s testimony are illustrated by the first-century historian, Flavius Josephus. In his Antiquities, Josephus states: ‘From women let no evidence be accepted, because of the levity and temerity of their sex’ (4.219).

While there may be other reasons to accept the historicity of the account, I personally do not find this argument persuasive. In this post, I unpack three reasons why.

1. Women were the natural witnesses to the empty tomb

The first problem with this argument is that it does not pay careful enough attention to the story Mark - the earliest example of this tradition - is trying to tell.

At this point of Mark’s narrative, all of Jesus’ male disciples have deserted him. It was Jesus’ female disciples who followed him to the cross (Mk. 15:40-41). So it is the women who - according to the logic of Mark’s narrative - knew the location of the tomb.

One might reply that if Mark’s tale is fictional, he could have told it in any way he wanted. For instance, he could have had the male disciples repent and appear alongside the women at the tomb, only to have their unbelief dissipate.1

Yet is that the story that Mark wanted to tell?

Commentators often point out that the disciples in Mark are a near-consistent failure. Sometimes their ignorance is exaggerated to the point of historical absurdity.

In this moment in Mark’s story, then, women are the only candidates for the job. The disciples will be restored, but this will take place in Galilee, as Jesus foretold (14:28).

And there is nothing surprising about finding women grieving Jesus. Mourning was the role of women in society. It is thus most natural to find women at the tomb.

2. Were women embarrassing to Mark’s Christian audience?

Another problem with this argument is that it assumes the testimony of women would have been embarrassing to the evangelist and his audience.

If we took Josephus as our standard, we might assume that female testimony was discounted in every instance. Yet we know this was not the case. As Carolyn Osiek points out, women’s testimony was acceptable in Jewish law in a range of scenarios.2

Yet Mark was not, in any case, written to make a defence to non-believers. The testimony of women did not need to ‘stand up’ to the scrupulous gaze of outsiders. Rather, the account was written for followers of Jesus.3

This is an especially important point given the role women played in early Christianity: ministering as apostles, prophesying and proclaiming the Gospel.

We see their important role reflected in John’s story of the Samaritan woman: ‘Many Samaritans from that city believed in him because of the woman’s testimony , “He told me everything I have ever done”’ (4:39).

Here the word ‘testimony’ is the same used by Josephus. So is it true that a woman’s testimony could not be accepted?

3. The criterion of embarrassment does not guarantee authenticity

Finally, embarrassment is an important principle to take into account when reasoning historically.

Yet it is not a guarantee of historicity. In this sense, recent scholarship is right to describe the quasi-scientific language of ‘criteria of authenticity’ as misleading.4

In the case of the empty tomb stories, there are other data to take into account, which may outweigh embarrassment alone. Here I list just three points to consider:

First, it is not the consensus of modern scholarship that Jesus’ corpse was interred in a tomb. That Jesus’ corpse was buried and not left to decay on the cross seems almost indisputable, given the early formula of 1 Corinthians 15.

However, it remains debatable whether Jesus was buried in a tomb. Craig Evans and Dale Allison make powerful arguments in the tradition’s favour.5 While others think it is more plausible that he was placed in an unidentifiable common grave.6

Second, stories of a disappearing body and/or empty tomb are a common trope in antiquity, which I have discussed here. These stories, which Richard Miller calls ‘translation fables’, signal a hero’s ascension into heaven as a god.

This makes one wonder whether the empty tomb tradition, beginning with Mark, is a later attempt to concretise the earliest post-mortem confession of Jesus’ divinity, rather than a straightforward historical account.

Finally, the Gospel accounts feature elements which strike the modern reader as untypical of sober history and as lacking verisimilitude. For instance, in Mark, the women go to the tomb with spices, but with no means of accessing the tomb. This provides the perfect set-up for the angel to have rolled the stone away.

An Argument to Retire?

So, is it time to retire the argument from embarrassment of the woman’s testimony?

I have put forward three reasons why it might be:

The women at the tomb were the most fitting candidates for the role, given their social function and place in Mark’s narrative.

It is not the case that women’s testimony would always have considered invalid; this is especially true to Mark’s audience, comprised of Jesus followers.

The criterion of embarrassment is not, in any case, a guarantee of historicity; it has to overcome the significant historical issues associated with the accounts.

What do you think? Let me know in the comments section below.

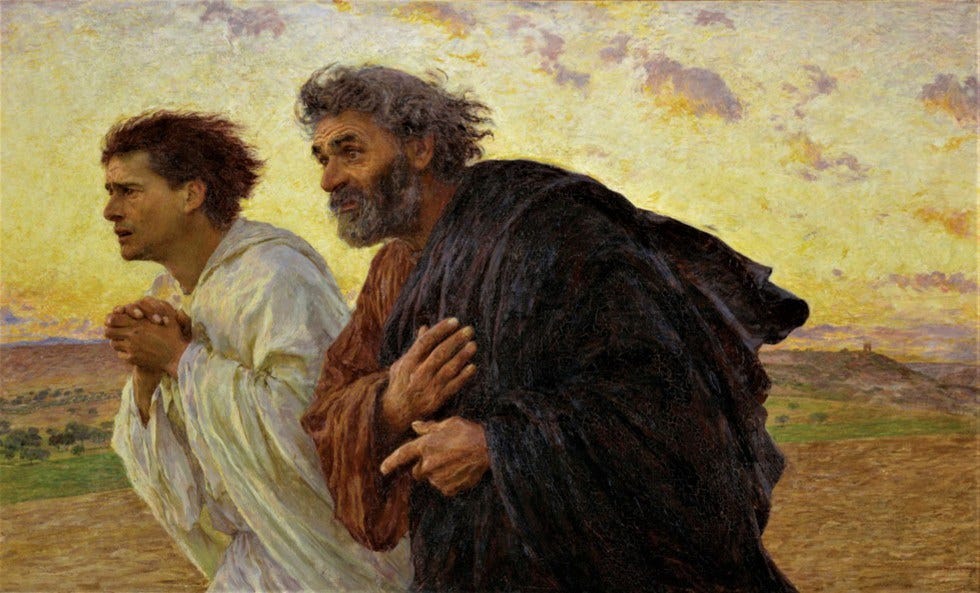

This is, in fact, what plays out in some later Gospel accounts. Luke has Peter check the women’s testimony, while John has Peter and the beloved disciple arrive at the tomb. This initially seems to support the idea that the testimony of women was inadequate.

Carolyn Osiek, “The women at the tomb: What are they doing there?” HTS 53 n.1/2 (1997): 112-113.

Helen K. Bond, “Was Peter behind Mark’s Gospel?” in Peter in Early Christianity, eds. Helen K. Bond, Larry Hurtado (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2015), 52.

See the essays in Anthony Le Donne, Chris Keith (eds.), Jesus, Criteria, and the Demise of Authenticity (London: T&T Clark, 2012).

See Craig A. Evans, “Jewish Burial Traditions and the Resurrection of Jesus,” JSHJ 3 n.2 (2005): 187-202; Dale Allison, The Resurrection of Jesus: Apologetics, Polemics, History (London: T&T Clark, 2021).

See, for example, Helen K. Bond, The First Biography of Jesus: Genre and Meaning in Mark’s Gospel (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2020).

A couple things. I don’t think anyone thinks that the criterion of embarrassment is ever a knockdown. It’s merely one criteria to determine historicity. Interestingly, Bart Ehrman Has floated the idea that it was early Christian women who invented the story of the women at the tomb to upgrade their clout among their male counterparts. I found this humorously ironic because Bart is countering the criterion of embarrassment by saying essentially, “ Well, you know women probably made up the story because you know how women are…” not that I think he consciously thinks that way, but it is kind of funny.

Also, I don’t find that the women doing something like going to assume that they didn’t think they could access is unrealistic. These are fervently believing women who are grieving. They are going to do some irrational stuff. In any case they could’ve thought that there would be someone there (Remember Mary Magdalene thought there was a gardener on site) who could help them. This was not an optional task to them. This was something that must be done for a loved one within a certain time after death, it was a cherished Jewish tradition. I’m sure in their mind they must at least make the attempt. Strict verisimilitude is something we look for in historical fiction. We shouldn’t be surprised to see humans humaning in historically accurate accounts.

Scholars have been going back-and-forth as you know re. how seriously Women’s testimony has been discounted in first century Jewish culture. As a result of writing a paper during my postgrad on this very topic, I’ve come to the conclusion that it should be taken pretty seriously.

Your point is well taken that this gospel may not be targeting unbelieving fellow Jews at all. Well, Actually, it would seem strange given the problems that Christian Jews were having with nonbelieving Jews in the mid to late first century that the gospel writers wouldn’t try to make the Messiahship of Jesus seem as plausible as possible, Even in their own Internal writings. Jewish Christians were to varying degrees at different times during this period, subject to pressure to reject their faith and integrate back into mainstream Judaism. The gospel writers may have wanted to reinforce the readers faith.

Anyway, nice post I enjoyed it.

Is this the same as this one?

https://www.behindthegospels.com/p/women-witnesses-at-the-tomb-an-argument