Jesus and Vespasian: The Public Ministry

Is the Markan Jesus distinctly Flavian?

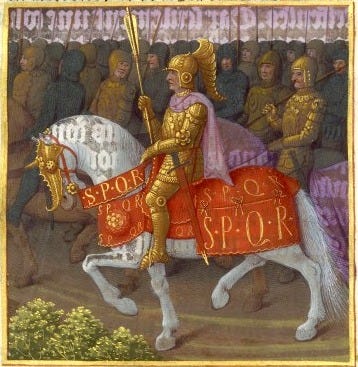

In the first century, there was a Son of God whose arrival brought ‘good news’ throughout the Roman world. He possessed miraculous powers, healing a blind man with spittle; he provided generous benefaction, feeding thousands; and he was indirectly responsible for the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple in 70 CE, following which he embarked on a triumphal procession, decked in kingly array. After his death, he underwent an apotheosis, and was deified.

His name was Vespasian - and in 69 CE, his rise to power spelt an end to the rule of Julio-Claudian Emperors and the beginning of his own Flavian dynasty.

Those interested in the Gospels will immediately note that Vespasian’s ascendancy overlaps with the conventional dating of Mark, around 70 CE. It would be no surprise, then, if Mark shaped his story with Vespasian to some degree in mind.

Scholars have long noted parallels between Vespasian and Mark’s Jesus. But more recently, Adam Winn has gone further to argue that Vespasian’s life comprises a hermeneutical key in unlocking the Gospel.1 When we read the Gospel ‘under’ Caesar, various unusual aspects of Mark’s narrative are thrown into clear relief.

In this series, we have seen how the evangelists drew upon familiar models in composing their stories. Luke drew upon aspects of the story of Aesop, John drew upon Dionysus, and both Matthew and Luke seem to have employed a familiar model in their infancy narratives, the sort told of Augustus and Alexander the Great.

Did Mark also draw on aspects of Vespasian’s life to compose his story of Jesus? In this two-parter, we take a look at seven Vespasian-like features of Mark’s Jesus, beginning – in this post – with Jesus’ public ministry.

1. The Good News of God’s Son

It does not take long before we stumble into imperial imagery in Mark. Note the incipit: ‘The beginning of the good news (euangelion) of Jesus Christ [Son of God]’.2

For those familiar with the Jewish Bible, these words would recall the ‘good news’ of Isaiah. But for all readers, the term ‘good news’ also had an imperial flavour. Compare, for example, the opening words of Mark with the Priene Calendar Inscription. The stone inscription, from 9 BCE, proclaims the birthday of the ‘god’ and ‘saviour’ Emperor Augustus as the ‘beginning of the good news for the world…’3

The term ‘good news’ was also used in reference to the accomplishments of later Emperors. For example, the Jewish historian Josephus notes that upon Vespasian’s accession to the throne, ‘every city celebrated the good news (euangelia) and offered sacrifices on his behalf’ (War 4.10.6 §618). From Mark’s opening sentence, it appears that Jesus, not the Emperor, is the one who brings good tidings to the world

This counter-imperial claim could also be heard in Mark’s reference to Jesus as God’s son. Whether or not the words ‘Son of God’ in Mark’s incipit are original, Mark refers to Jesus as the Son of God at key moments throughout the text (e.g. 1:11; 9:7).

This is significant, for the Emperor was also known as God’s son: divi filius. By announcing the good news of the Messiah – the saviour – who is God’s son, readers would immediately see that Jesus is being fashioned in imperial array.

2. Healing by Spittle

The concept of the ‘good news’ about a salvific ‘Son of God’ may not tie Jesus to any particular Emperor. Yet in Jesus’ healing ministry, we find something more distinctly Vespasian-like.

In his Life of Vespasian, Suetonius reports that Vespasian had healing powers. What is striking is the affinity Vespasian’s miracle bears to Jesus’ miracles in Mark:

A man of the people, who was blind, and another who was lame, together came to [Vespasian] as he sat on the tribunal, begging for the help for their disorders which Serapis had promised in a dream; for the god declared that Vespasian would restore the eyes, if he would spit upon them, and give strength to the leg, if he would deign to touch with his heel. Though he had hardly any faith that this could possibly succeed, and therefore shrank even from making the attempt, he was at last prevailed upon by his friends and tried both things in public before a large crowd; and with success… (7.2-3).

For a long time, scholars have wondered why Mark’s Jesus heals a blind man using spittle. This is not his usual modus operandi when it comes to healing. If Mark is casting Jesus as a Vespasian-esque figure, however, it begins to make sense.

According to Oxford biblical scholar Eric Eve, this story of Vespasian’s healing arose at the end of 69 or early 70 CE.4 At the time, it was used as propaganda to legitimate his ascension to the throne. Moreover, for Jewish ears, this scene could easily have sounded like a usurpation of traditional messianic hopes.

Two elements of this context should prick our ears. First, many scholars date Mark just after the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple in 70 CE. If this is correct, then Mark was written at just the right time to be influenced by the Vespasian episode. This Vespasian propaganda would have been floating around Mark’s setting.

Second, if Vespasian’s healing of the blind might have sounded a little too close to the fulfilment of Messianic expectations, we can understand why Mark placed the healing episode where he does: at the start of his teaching block of material (chs. 8-10). For, as is well known, the gradual healing of the blind man, which opens this section, serves as a metaphor for the disciples’ realisation that Jesus is the Messiah.

The big difference is the type of King that Vespasian and Jesus will be. While Vespasian inaugurated his rule through military victory, Jesus’ own kingship will be manifest in his own suffering and death.

3. Jesus’ Power over ‘Legion’

It is not as though Jesus is without his own conquest in Mark, however. Possible clues that Jesus is a counter-Vespasian are also left in another miracle-story: Jesus’ power over the demon named ‘Legion,’ which he chases into a herd of pigs. None of the Roman Emperors were thought to be exorcists. But several things about this story might make us think of Rome generally, and Vespasian in particular.

To begin with, the term ‘legion’ denotes a cohort of 6,000 Roman soldiers. While this connection between the demonic forces and Rome may seem incidental, it is one that was also made in the first-century by John, in the book of Revelation.

Strengthening this link, Mark uses war-like terminology to describe the legion of pigs.5 For example, he uses the verb ὁρμάω, a word which often denotes a military charge, to describe the rush of pigs into the sea. And he uses the term agele (άγέλη), which is often used of a military troop, to describe the ‘herd’ (5:13).

None of this may seem especially Vespasian-like, beyond the general point that Vespasian’s claim to the throne was martial rather than hereditary. But a further detail may betray a connection to Vespasian: Vespasian was in charge of the Roman legion which destroyed Gerasa during the Jewish revolt. And the banner that the tenth legion carried as they destroyed the city was that of the bore - a pig!6

Early readers may therefore have seen here a thinly veiled anti-Vespasian critique. While Vespasian had control of physical legions, Jesus had total control of a ‘legion’ of demons which, in its location and symbolism, evoked Vespasian.

4. Nature Miracles

A fainter set of imperial echos may also be heard in Jesus’ ‘nature miracles.’ Take, for example, Jesus’ ability to control the waves and walk on water. There are clear allusions here to YHWH’s distinct ability in the Hebrew Bible to control the sea.

But some of the Roman Emperors were also believed to have ruled the waves. Caesar Augustus, for example, was said to have brought peace to the sea. As Philo writes, “This is the Caesar who calmed the torrential storms on every side... This is he who cleared the sea of pirate ships and filled it with merchant vessels” (Gaius, 145-46).7

The Roman Emperors were also known for their benefaction, supplying money and grain in times of need. As ‘Father of the Country’, Caesar Augustus claims in his Res Augusta to have given out generous supplies of grain in times of hunger (15.1-4; 18.1). Similarly, when Vespasian secured the throne, the city of Rome only had ten days of grain left. To save the population from starvation, the Emperor imported grain from Alexandria, a city regarded as his personal possession. 8

While they do not provide a close parallel, some of these imperial actions may be faintly heard in Jesus’ own benefaction: his generous supply of fish and loaves to the masses in Mark’s feeding narratives. This affinity would be particularly apparent if the traditional authorship of Mark in Rome is correct, as Winn has argued at length.

5. The Messianic Secret

Finally, the idea that Mark’s Jesus is Vespasian-like may also help to unravel a curious thread which runs through Mark: the so-called ‘messianic secret.’ This is the tendency of Jesus to keep his identity a secret and demand secrecy from others too.

In recent scholarship, the Messianic secret has been read as less about secrecy and more as Jesus’ intentional resistance to receiving honour.9 There are a number of healing episodes, for example, in which Jesus stands as a patron would to a client. But instead of receiving honour for his benefaction – as one might expect of an ancient client – Jesus commands those he has healed to remain silent (e.g. 1:40-15; 7:31-37).

This is an intriguing reading, but there is a problem with it: it is not sustained throughout the Gospel. While Jesus at times deflects honour, at others he embraces it (e.g. 1:21-28; 11:10).10 How can we explain this inconsistency?

Winn has argued that seeing Jesus as an Emperor-type can help us.11 For like Jesus, the Emperor was regularly known to deflect honour, as well as to receive it. In a strategic move for the Princeps, the Emperor would give the impression to freedom-loving Romans that he was merely a “first among equals” by rejecting honour.

Vespasian, for example, was hesitant to accept the title ‘Father of his Country’ or his tribunician powers (Vesp. 12).12 He also seems to have ended the traditional practice of Romans worshiping the guardian spirit, or “genius” of the living emperor, which had been instituted by Caligula.13 Some readers of Mark may therefore have understood Jesus’ refusal to accept honour as a Vespasian-esque move.14

Far from keeping his identity a total secret, Jesus – like the Emperor Vespasian – at times embraced and at others deferred the honour his elevated status entailed.

This is the end of part one, but just the beginning of the parallels between Jesus and Vespasian. If you enjoyed it and would like to find out what Jesus’ death has to do with the Emperor, consider becoming a paid subscriber using the link below.

See Adam Winn, The Purpose of Mark’s Gospel. WUNT 245 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2008). For a popular treatment, see Adam Winn, Reading Mark’s Christology under Caesar: Jesus the Messiah and Roman Imperial Ideology (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2018).

It is contested as to whether the words ‘Son of God’ are original. See Craig A. Evans, “Mark’s Incipit and the Priene Calendar Inscription: From Jewish Gospel to Greco-Roman Gospel,” JGRChJ 1 (2000): 67-81 (67-68).

See Evans, “Mark’s Incipit,” 67-81 (69).

See Eric Eve, “Spit in Your Eye: The Blind Man of Bethsaida and the Blind Man of Alexandria,” NTS 54 (2008): 1-17.

See Winn, Reading Mark’s Christology, 84.

Ibid., 84.

Roman inscriptions praise Augustus as the ‘overseer of every land and sea’, a sentiment also seen in the Roman poets. See Peter Bolt, Jesus’ Defeat of Death: Persuading Mark’s Early Readers (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 132-33

See Barbara Levick, Vespasian (London: Routledge, Í999), 124-25 cited in Adam Winn, “Resisting Honor: The Markan Secrecy Motif and Roman Political Ideology,” JBL 133 n.3 (2014): 583-601 (599).

See particularly David F. Watson, Honor among Christians: The Cultural Key to the Messianic Secret (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2010).

Winn, “Resisting Honor,” 585.

Ibid., 583-601.

Ibid., 592.

Ibid., 592.

One of the difficulties with this reading, pointed out by Daniel Glover, is that not every instance of the Messianic secret seems to be linked to honour. One example Glover gives is Jesus’ transfiguration (9:9). See his review of Winn’s book on Reading Religion. https://readingreligion.org/9780830852116/reading-marks-christology-under-caesar/

Michael Bird argues (quite convincingly imo) that Jesus' words in Mark about 'the kingdom coming with power' were in reference to His crucifixion. If so, this reversal of what power was presumably understood to look like fits nicely alongside these potential nods to the emperor and Roman manifestations of power.