What was Jesus' Hometown Really Like?

Three Insights from First-Century Nazareth

The environs, moreover, are charming; and no place in the world was so well adapted for dreams of perfect happiness. Even in our times Nazareth is still a delightful abode, the only place, perhaps, in Palestine in which the mind feels itself relieved from the burden which oppresses it in this unequaled desolation. The people are amiable and cheerful; the gardens fresh and green. Anthony the Martyr, at the end of the sixth century, drew an enchanting picture of the fertility of the environs, which he compared to paradise.”1

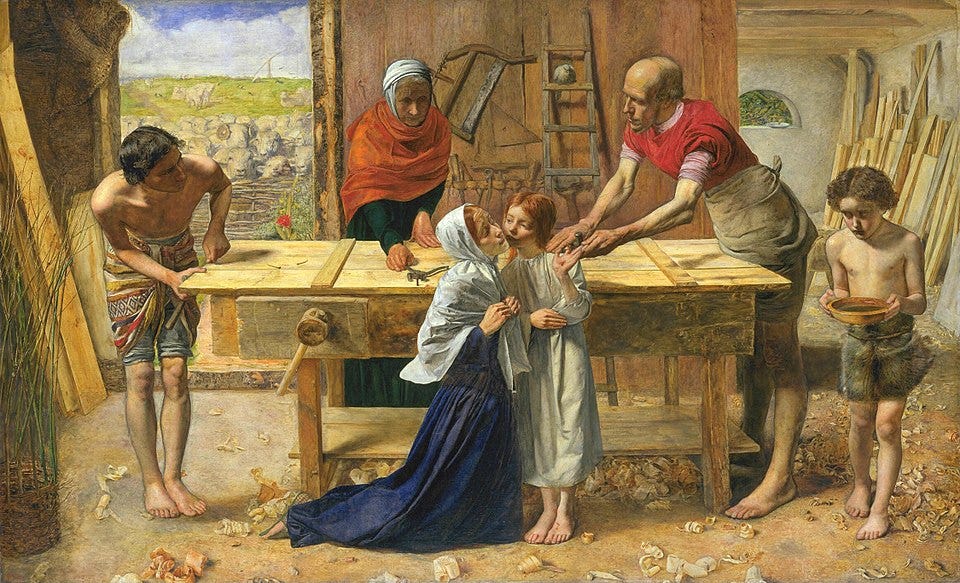

This English translation of Ernest Renan’s Vie de Jésus captures perfectly the romantic feeling of the 19th century liberal lives of Jesus. It constructs Nazareth as the cradle of a gentle Jesus, of the kind Millais portrays in Christ in the House of the Carpenter.

Yet Renan was not alone in idealising Nazareth. His contemporary, Frederick Farrar, also points to the natural beauty and fecundity of Jesus’ hometown:

In spring, at least, everything about the place looks indescribably bright and soft; doves murmur in the trees; the hoopoe flits about in ceaseless activity; the bright blue roller-bird, the commonest and loveliest bird of Palestine, flashes like a living sapphire over fields which are enamelled with innumerable flowers. And that little town is En Nâzirah, Nazareth, where the Son of God, the Savior of mankind, spent nearly thirty years of His mortal life. It was, in fact, His home…”2

In these works and others, Jesus emerges like a romantic poet – uncorrupted by the world and its influences, he spent time in the beautiful environs of Nazareth.

As we will come to see, this is hardly a complete portrait of what life in first-century Nazareth was like. Yet there is a truth in the instinct to describe Nazareth in this way: where Jesus grew up would have undoubtedly affected his life.3 Thus, while it may be easy to dismiss these romantic portraits of a gentle Jesus, it is harder to deny the importance of Nazareth for understanding his early life and formation.

Approaching Ancient Nazareth

But what do we actually know about Nazareth? The name of the town appears nowhere in the Hebrew Bible, in contemporary Jewish or later rabbinic literature. And when it turns up in the Gospel of John, Nathanael asks whether anything good can come from it. Clearly, whatever Nazareth was, it was not a bustling metropolis.

At the same time, all is not lost. In fact, it may be that we now know more about first-century Nazareth than we have done for a very long time. Over the last three decades, Nazareth has undergone fieldwork by archaeologist, Professor Ken Dark. When Dark showed up at the site in 2006, it was to excavate Nazareth as a centre of Byzantine pilgrimage. Yet to his amazement, he stumbled upon a layer which revealed a number of new insights on the first-century town.

Dark’s work has now been published as a fascinating volume by Oxford University Press, The Archaeology of Jesus’ Nazareth.4 In what follows, I want to draw on some of Dark’s discoveries to reveal the kind of place that Nazareth was. But before we get to that, I want to probe further into the name of Nazareth itself.

What’s in a Name?

The name Nazareth contains its own puzzle. It derives from the Hebrew Nazar, which means ‘branch’, ‘shoot’ or ‘root.’ This is the same word found in Isaiah:

‘A rod shall come out from the stump of Jesse,

and a shoot (וְנֵ֖צֶר) shall grow out of his roots’ (11:1)

Why was Nazareth known as the place of the ‘root’? While I don’t think we can know for certain, I am very intrigued by a possibility that scholars have sometimes raised. This is the idea that Nazareth was a town expecting the ‘nazar’ of Jesse to emerge.

Such a proposal may, admittedly, seem speculative. But there are a couple of data points which may help us to see that it is not completely far-fetched.

The most important is that Nazareth was a thoroughly Jewish place – and that Galilee had not always been this way. Isaiah describes Galilee as ‘Galilee of the Gentiles’, reflecting the idea that the (northern) tribes of Israel had long since dispersed. So what happened to lead Jews to occupy the North – to Galilee – again?

The key turning point seems to have been the Jewish revolt against their Greek leaders in the first half of the second century BCE. Having pushed off the gentile yoke, Judeans (‘Southerners’) began to migrate to the North. These gave an influx of migration and new towns were populated, like Jesus’ hometown, Nazareth.

This migration could have held profound theological meaning. In a similar way to how Israeli settlers today might see themselves embarking on a theological project – restoring Israel to Israel – so the Judeans who established Nazareth could have seen themselves as participating in the renewal of Israel. Several texts from the Second-Temple period portray the re-constitution of Israel as a mark of the messianic era.5

If this suggestion is along the right lines, it could have impacted Jesus in a number of ways. It could mean that the very atmosphere of Nazareth was one in which piety was taken seriously – and in a moment, we shall see that this was the case. But it could also have shaped his theological imagination. He may have had a sense, early on, that Israel really was coming together. The calling of his own group called ‘The Twelve’ may be seen as an extension of the general atmosphere in a place like Nazareth.

Yet there is another feature which could point us in this direction. There is a tradition already in Paul that Jesus was of the ‘Seed of David’ (Rom. 1:3). If Jesus was of Davidic descent, if Jesus’ father – and perhaps others in Nazareth – had treasured their (southern) links to this lineage, we may have a further sense of how Jesus could come to see himself as a potential key player in the burgeoning Kingdom of God.

Jesus’ Early Religiosity

We have talked a little bit about Nazareth in connection to messianic expectations. But can Nazareth tell us anything about the day-to-day religious life of Jesus?

One feature of religious life in Nazareth mentioned in the Gospels is its synagogue. Luke paints us a picture when he writes that ‘He came to Nazareth, where he had been brought up; he went to the synagogue on the sabbath day, as was his custom…’

The difficulty is that the extensive excavations of Nazareth has shed no light on this synagogue. There may be a few explanations for this. One is that there was a synagogue, but it has no longer survived. But it may also be that the synagogue does not refer to a literal building – of the kind we find in Capernaum – but rather a gathering of people. This is what a ‘synagogue’ literally is – a ‘gathering together.’

Regardless, there is no good reason to doubt that the townsfolk of Nazareth were in the habit of meeting on the Sabbath to hear scripture read aloud. There is a debate about whether Jesus was literate or not. Yet these gatherings in the synagogue may well have provided Jesus’ first exposure to the scriptures which shaped his ministry.

Another element to religious life in Nazareth was Torah observance. As in other places, Nazareth contained limestone vessels. This is significant because limestone was thought to be immune from ritual impurity. We find this thought in rabbinic texts. For instance, the Mishnah states that ‘all utensils become unclean through contact with impurity, except those made of dung, stone, or earth.’ (Kelim 10:1).

The fact that Nazareth contained limestone vessels is not peculiar to Nazareth. Yet there is another datum which points to a strong sense of Jewish identity: all of the products which were made in Nazareth were made by Jews. This stands in sharp contrast to the more cosmopolitan environment of Sepphoris, six kilometres away.

One might question: how can Nazareth and Sepphoris be so close by and yet have such a different material culture? Ken Dark explains:

“…. those people who lived near, and in, Nazareth emphasized their own Jewish culture and identity. They seem to have actively resisted the market forces and cultural imperialism of the Roman province. In fact, Nazareth… may form the most clear-cut example of local people resisting Roman imperial culture anywhere in the Roman Empire.”6

Let us take a pause here. Dark says that Nazareth and its surrounding towns may be the most resistant economies to Roman imperial culture “anywhere in the Roman Empire.” He goes on to infer from this the following:

“This itself implies that Nazareth was more than just an insignificant hamlet. It was in some sense a focus for Jewish communities in the valley, in opposition to pro-Roman Sepphoris. This may be seen also in economic terms, with communities which avoided contact with Sepphoris and its culture using Nazareth as a centre for the local economy.”7

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Behind the Gospels to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.