The Missing Years of Jesus

What really happened in Jesus' childhood?

What was Jesus up to before his baptism?

The Gospels tell us very little. Which is unsurprising. Most biographers of the time either jump straight into the adult life of their subject, or provide us with only fleeting glimpses of their subject’s background before fast-forwarding to their adulthood.

Yet historically Christians have not been satisfied with the Gospels’ silence.

One story, from the second century CE, tells of a ‘boy’ Jesus who had already found his supernatural powers, cursing a young nemesis to death, and making real-life birds from clay.1 Such Christian fan-fiction ended up finding its way into the Quran.2 But it hardly advances our knowledge of the missing years of Christ.

Are we to throw our hands up, then, and admit that we cannot know anything about Jesus’ missing years, before his baptism around thirty? (Lk. 3:23).

While it is difficult to draw hard-and-fast conclusions, there are some clues we can gather from the Gospel accounts. In this post, I want to see where they’ll lead.

Boy Jesus in the Temple

The only reference to Jesus’ childhood in the Gospels is found in Luke. In this episode, a twelve-year old Jesus goes missing from his parents on a trip in Jerusalem. When it comes time to return, Joseph and Mary realise that Jesus has not been tracking.

Eventually, in something of a spiritual ‘home-alone’ scenario, Jesus is found in the Temple. To his very distressed parents, who wonder where he has been, the child ripostes, where else but in his Father’s house!

Luke describes what the precocious twelve-year old had been up to as follows:

‘After three days they found him in the temple courts, sitting among the teachers, listening to them and asking them questions. And all who heard him were amazed at his understanding and his answers. (Lk. 2:46).

What are we to make of this story? On the one hand, it seems plausible enough. I teach at a boys’ school, and I regularly encounter students who school me - ‘Dr Nelson’ - with their ‘listening’ and ‘asking of questions.’

Yet the story of a ‘boy’ Jesus - who is already up to the activities which will occupy his adult life - also gives the feeling of a ‘stock’ tale. In other ancient lives, we find similar stories in which retroject some aspect of the character’s adult life back into their childhood.

Take, for example, Xenophon’s Cyropaedia, an early Greek biography of the Persian King, Cyrus. Opening the life, Xenophon tells us that the twelve-year old had a ‘rich love of learning… such that he always inquired from everyone he met the explanation of things… He himself was asked questions by others on account of his intelligence, and he himself answered with alacrity.’3 Luke begins to sound very familiar.

Or consider a near-contemporary biography to Luke, Plutarch’s Alexander. Towards the beginning of the life, Plutarch tells the story of a young Alexander, taming a wild horse. It was this moment that Philip, his father, recognises his son’s sons stature:' My son, seek thee out a kingdom equal to thyself; Macedonia has not room for thee.’4

Such stories reflect an idea that a hero was by nature what they would later ‘become.’ In such cases, it is possible that the biographer may have worked backwards from a subject’s adult life, and assumed that something of this sort must have occurred in childhood. If this is the case, it is not clear how much history there is to such tales.

The episode does, however, broach the question of Jesus’ education. In this pericope, we find a Jesus who is at home in the ‘classroom’ of a Temple education. But would Jesus have received an education?

As I have shown elsewhere, scholars are divided on the issue. Some scholars have supported the picture of a literate Jesus. Maurice Casey, for instance, questions the odds of two major Jewish religious leaders - Yeshua ben Joseph and James the Just - could have emerged from the same family without a strong educational background.5

Yet others question the reconstruction of a highly literate Jesus. In the most comprehensive study of the question, The Literacy of Jesus, Chris Keith reminds us that education in antiquity was largely reserved for the elite; without a public education system, the vast majority of the ancient world was, to varying degrees, illiterate.6

In Keith’s view, no story in the Gospels offers unequivocal evidence that Jesus could read and write. It is possible, then, that Jesus mostly heard the Scriptures, and that his literacy never rose to the level of a very literate person. While Jesus would have spoken Aramaic, it is unlikely that he had more than a cursory knowledge of Greek.

Perhaps the most plausible element of this story is the that Jesus visited Jerusalem as a boy for the festival with his family. Such was the course for many tens of thousands pilgrims from Galilee in the North. And there is no good reason to think Jesus was any different. These early experiences in the Temple would undoubtedly have conveyed a sense of its importance, which his ministry would display.

Ship-Building? Theatre Construction?

If Luke provides us with no more than a ‘stock’ snapshot of Jesus’ childhood, then perhaps we may be on firmer footing with Jesus’ adult profession.

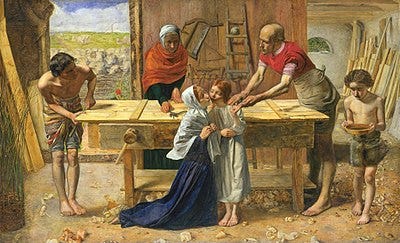

Matthew describes Jesus as the ‘son of a carpenter [tektōn]’ (13:55), while the earliest Gospel, Mark, is even more realistic in describing Jesus himself as the labourer (6:3). (One cannot but wonder if Matthew’s 'son of a carpenter,’ while not lacking verisimilitude, is an attempt to distance Jesus from the mundane role.)

Traditionally, the word tektōn has been translated ‘carpenter.’ This produces the classical depictions of Jesus in his father’s workshop. Yet as John P. Meier notes, the term can refer more broadly to anyone who works with hard materials, including stone.7 This widens the set of jobs which Jesus might have had.

Where might Jesus have worked, and what would he have done? One common suggestion is that Jesus worked in nearby Sepphoris, just four miles north of Nazareth. Perhaps the most intriguing feature of this city is its Greek theatre, which some date to the reign of Herod Antipas (4 BC-39 CE), a ‘Hellenistic’ innovation in imitation of the large-scale building projects of his father, Herod the Great.

With this city nearby, some scholars have surmised that Jesus may have visited or even played a part in building this theatre. This theory is apparently lent support by Jesus’ common accusation that religious leaders were hypokritai - quite literally, ‘stage actors’. It has also seemed to explain where he initially imbibed the dramatic flare and anti-institutional rhetoric which later characterised his ministry.8

I find this scenario quite unlikely, and the evidence specious. To begin with, a first-century date of the theatre is far from certain, with some leading archeologists dating it after the Temple’s destruction in 70 CE.9 Moreover, while the term ‘hypocrite’ may have originally referred to actors on stage, it is not used in the Gospels in this theatrical sense. By the time of Jesus, the Greek word had taken on a generally negative meaning, like it has today; someone who pretenders. In Hebrew, it simply meant an evil-doer.10 So Jesus did not acquire the term from the theatre.

The evidence that Jesus attended the theatre also faces challenges. As Markus Bockmuehl notes, “[this] possibility must be balanced generally against the opposition to pagan theatre in conservative circles at this time.”11 If Jesus was from a pious Jewish family (see below), it is likely he avoided such institutions. It is striking that the Gospels never refer to the major Greek cities of Galilee. Could it have been that it was always natural for Jesus to avoid these more palpably Hellenised locations?12

While Jesus was not probably a theatre-builder, working in nearby Sepphoris, scholars have considered other jobs he may have done. Recently, Jesus historians Helen Bond and Joan Taylor observed that a lot of Jesus’ activity takes place around the lake of Galilee. They suggest that Jesus may have had something to do with the fishing trade, perhaps as a boat-builder.13 One boat from around the period, dubbed the ‘Jesus Boat,’ gives us some indication of the sort of ships Jesus may have built.

It is also plausible that Jesus and his father worked in Nazareth itself. As seasoned archaeologist, Ken Dark, reports, Nazareth in the first century was not solely a farming community; it had a mixed economy of farming, quarrying and craftsmanship, and it seems to have existed beyond subsistence level. In other words, it was “precisely the sort of place in which we might expect to find a tekton.”14

Religious Life in Nazareth

In addition to Jesus’ profession, Nazareth can also give us a glimpse into the religiosity of Jesus’ community. From the first century, various stone vessels have been found in Nazareth and other Jewish towns across Palestine. These vessels give us some insight into the piety of Jesus’ community, for unlike clay, stone could be re-used to keep food ‘pure’ according to the ritual purity of the Jewish law.

The piety of this community reminds me of a tantalising suggestion by a Professor that Nazareth saw itself as part of the re-constitution of Israel. The ten tribes in the North had long been dispersed. However, in the second century BCE, following the conquest of the Greeks by the Hasmoneans, Jewish communities began to emerge in the north again. A community which migrated north from Judea, which Nazareth may well have been, might therefore have seen itself as participating in Israel’s reconstitution, a sign thought to accompany the Messianic age.

This theory could be used to explain the name of the town, Nazareth, which plausibly derives from the Hebrew n-z-r (‘shoot’). Was this a community which anticipated the ‘shoot’ of David in Isaiah (11:1). It might also explain why Jesus would call twelve male disciples, who represented the twelve tribes of the reconstituted Israel. Jesus thought that this reconstitution was happening around his very person. Could his ‘Nazareth’ upbringing have played a part in forming this notion?

Whatever the likelihood of this intriguing theory, there is good evidence that Jesus would have attended synagogue - whether in a literal sense or as an assembly (a syn-agogue is a ‘bringing together’ of people.) Although there has been a fierce debate about whether synagogue buildings existed in the first century Galilee, the current consensus is that they did.15 It is quite plausible, then, that Nazareth had one too.

In terms of Jesus’ religiosity, it seems that at some point prior to his baptism, Jesus became a follower of John the Baptiser, whom Luke remembers as his relative (1:26). (It is often thought that John was Jesus’ cousin, but the text is not clear about Elizabeth’ relation to Mary.) This John was a rag-tag prophet, a cultural critic especially well known for calling out King Herod’s marriage to his brother’s wife.

A close connection between Jesus and John is supported by Jesus’ baptism, as well as a number of sayings which cast John in a highly favourable light - such as him being, in one sense, the greatest person to ever live (Lk. 7:38)! Jesus claimed that he received his authority from John, some of Jesus’ own disciples may once have been followers of the Baptist (John 1:35-40), and both figures also worked on the somewhat unusual assumption that forgiveness could operate outside the strictures of the Temple.

It is not surprising, then, that the Baptist’s most recent biography think that many of Jesus’ ideas came from the Baptist.16 While the two may not shared exactly the same vocation or vision of the Kingdom - Jesus did not share John’s Nazirite vow - Jesus did take up the mantel of John’s fundamental message: Repent, the Kingdom is near!

The Man of the House?…

If John’s familial relationship to Jesus remains somewhat unclear, we may have a better idea about his other relations. Mark explains that Jesus had brothers and sisters, but in typical patriarchal fashion, only the brothers are named: James, who appears elsewhere in Paul’s epistles as a pillar of the Church, Joses, Simon, as well as Judas (known in the tradition as ‘Jude’, to distance him from Jesus’ betrayer; 6:3).

In the Catholic tradition, these ‘brothers’ and ‘sisters’ are not regarded as Jesus’ real family. Committed to the perpetual virginity of Mary — the view that Mary remained never had sex — these ‘brothers’ and ‘sisters’ are sometimes thought to be cousins of Jesus, or perhaps step-siblings from a previous marriage of Joseph.

Neither suggestion is a natural reading of the text. The Gospel does not claim that they were cousins - for which there was a word in Greek - but rather brothers and sisters. And the idea that these were not biological kin of Mary also strains credulity. Not only does the evidence that Mary was a perpetual virgin later, from historically dubious sources, the text only mentions Jesus’ kin in relation to Mary.

It is striking, however, that Jesus is mentioned in the same verse as the ‘Son of Mary.’ Why is this? The common explanation is that by this point, Jesus’ father was out of the picture. I find this plausible. The average life span of a man in Jesus’ time was just over twenty years; the work Joseph did could be dangerous, and Galilee in this time was undergoing something of a “chronic health crisis.”17 In a world marked by sudden death, it is wholly unsurprising that Jesus’ father was not on the scene during his public ministry.

What does this mean for Jesus’ upbringing? If Jesus was the eldest child, he may have had to comfort and care for his siblings as head of the home. In the Gospels, Jesus often assumes the role of paterfamilias - in hosting suppers and the Passover - and it may be that he had long assumed this role of authority from his early life.

At the same time, it does seem that Jesus was not one to overstate the importance of his biological kin. Some of his teachings relativise the importance of his family (anyone who does the will of God is his true family) and shockingly eschew the importance of practices like burial (‘let the dead bury their own dead.’)

This is consistent with Jesus’ own decision to remain unmarried - a move which was unusual and slightly ‘unmanly’ but not wholly unprecedented. The likely reason for this are provided by a saying in Matthew: ‘For there are eunuchs who were born that way… and there are those who choose to live like eunuchs for the sake of the kingdom of heaven’ (19:12).

Jesus seems to have fallen into the latter category. If he ‘made himself a euenech for the kingdom’, his sense of spiritual vocation may have developed early on.

Filling in the Silence Today

People are still filling in the gaps of Jesus’ missing years. Only one of the most recent suggestions (which sounds like it is ancient) is the idea that Jesus went from Egypt to India, and spent time with Hindu Brahmans. This is where he learnt his tricks.

Why is there such a strong desire to fill in the silence?

Partly, I think the instinct arises to understand how this person became who he did. We already see this in Luke’s Gospel, which, if not entirely historical, does something completely normal in imagining how Jesus could have acquired his skills.

The ‘missing years’ of Jesus are also fertile soil to depict a very different sort of Jesus to the one traditionally imagined. In one sense, this can be positive: it reminds us, as historians, how how little we know about the historical Jesus, and how much imagination - which can be so fruitful, spiritually - is necessary to the historical task.

On the other hand, it can be dangerous to create a Jesus wholly in our image. The danger for Jesus scholars has always been that we look down the well of history and find our own reflection staring back at us. We know that we have ceased doing history when we have no sense of the marked difference of Jesus’ own world.

For me personally, I find the activity of imagining Jesus’ childhood a deeply humanising one. To think that he would have erred in his parents’ eyes, learnt a trade, attended synagogue, or even comforted his siblings after the loss of their father, means that he was (to quote one early writer) ‘like us in every sense, apart from sin.’18

In this post, I have tried to give a brief tour of what Jesus’ life might have been like, drawing upon some of the best scholarship. I am sure there is much still to be said.

See the Infancy Gospel of Thomas for many fantastical stories of Jesus’ childhood.

Quran 3:49; 5:110.

Xenophon, Cyropaedia. 1.1, 1.3.4-1.4.3.

Plutarch, Alex. 6.5.

Maurice Casey, Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian’s Account of His Life and Teaching (London: T&T Clark, 2010), 42.

See Chris Keith, Jesus’ Literacy: Scribal Culture and the Teacher from Galilee, LNTS 413. (London: T&T Clark, 2011).

John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, vol.1 (New York: Doubleday, 1991), 278-85.

See Richard A. Batey, “Jesus and the Theatre,” NTS 30 n.4 (1984): 563-574.

Carol L. Meyers, Eric M. Meyers date the theatre to the early second century (“The theater… seems to date to a period later than Antipas.”) See C.L. Meyers, E.M. Meyers, “Sepphoris,” OEANE 4:527-36 (530).

Frank Stern, A Rabbi Looks at Jesus’ Parables (Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield, 2006), 81.

Markus Bockmuehl, This Jesus: Marytr, Lord, Messiah, 2nd ed. (London: T& Clark: 2004), 192.

This possibility must be set against the evidence that Sepphoris was, in fact, a highly Jewish city. See, for example, Mark Chancey, Eric F. Meyers, “How Jewish Was Sepphoris in Jesus’ Time?” Biblical Archaeology Society, July/Aug 2000 [Online. Accessed 6th July: https://library.biblicalarchaeology.org/article/how-jewish-was-sepphoris-in-jesus-time/].

Helen K. Bond, Joan E. Taylor, Women Remembered: Jesus’ Female Disciples (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2023), 26.

Ken Dark, Archaeology of Jesus’ Nazareth (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023), 45.

Ibid., 137.

See James F. McGrath, Christmaker: A Life of John the Baptist (Cambridge, MA: William B. Eerdmans, 2024).

See Jonathan L. Reed, “Mortality, Morbidity, and Economics in Jesus’ Galilee” in Galilee in the Late Second Temple and Mishnaic Periods: Life, Culture, and Society, eds. David A. Fiensy, James R. Strange. Vol. 1 (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2014), 317-330; Joan E. Taylor, “Jesus as News: Crises of Health and Overpopulation in Galilee,” NTS 44 n.1 (2021): 8-30.

Hebrews 4:15.