Searching for Alexamenos

Is this the Earliest Depiction of Jesus Christ?

My friend and I were hiking the Palatine hill in Rome. Just four hours before our flight back to London, our prized destination was the Palatine Hill Museum.

But Rome wasn’t build in a day - and neither apparently was the Palatine Museum. Upon our sweaty ascent, we were met by a foreboding site. Scaffolding.

‘The second and third floors of the Museum are closed,’ the steward reported. But the image we wanted to see was on the second floor. So we strolled back through the gardens of Augustus, took a final look at the Arch of Titus, and went to get a pizza.

The Alexamenos Graffito

What was this pièce de résistance which seemed worth our trek up the hill?

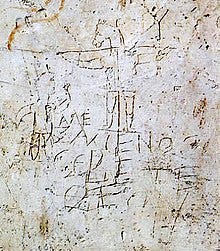

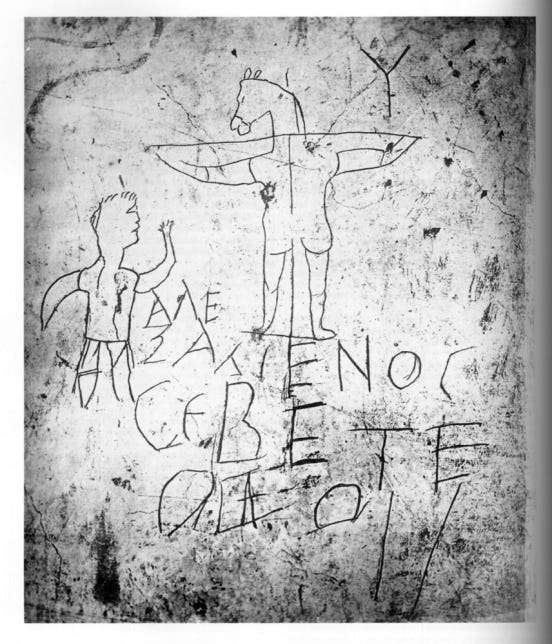

Often dubbed the Alexamenos Graffito, it is a slab of wall which displays two almost stick-like figures. On the left, there is a man with his hand raised in proclamation; on the right, there is a man on a cross, with a donkey’s head.

Between and below them, we find the Greek text: ΑΛΕΞΑΜΕΝΟϹ ϹΕΒΕΤΕ ΘΕΟΝ.

These words are often translated ‘Alexamenos worships his God.’ Yet the second word, sebete (‘worship’), is a plural imperative: it is an instruction to worship God.1

It seems then that Alexamenos – a convert to Christianity? – is being mocked; he is telling us to worship a donkey. The crucified man with a donkey’s head is Christ.

The Earliest Image of Jesus?

The graffiti, discovered on the south-western slopes of Palatine Hill in 1857, is often considered the earliest surviving depiction of Jesus. Yet this may not be the case.

Commonly, scholars place the image somewhere between the late first and early third centuries CE, with most preferring the latter date. If this is the case, then the graffito competes with another early image of Jesus: a gemstone in London’s British Museum.

Like the Alexamenos Graffiti, the gemstone also depicts Jesus on a cross - this time with his legs dangling oddly to the side - with accompanying text. Yet its words are not a taunt but an incantation. It opens with the words, ‘O Son, Father, Jesus Christ,’ before proceeding with a series of impenetrable magical words and vowels.

The purpose of this item – which might not have belonged to a Christian, per se – seems to be to channel the power of the cross and the divine name of Jesus. Set alongside the Graffito, it displays the very different perspectives on Jesus’ crucifixion people had in the ancient world - from foul mockery to magical manipulation.2

The Meanings of the Graffiti

Whether or not the Alexamenos is the earliest depiction of Jesus, it provides a tantalising window into perceptions of Christianity in the Roman Empire.

This year, at the boys’ school at which I teach, I taught an elective on the historical Jesus, and I showed my students this image to give an impression of the weirdness of the Christian claim - that Jesus, a divine man, should die a criminal’s death.

Crucifixion was a topic that could only be spoken about in Rome in the most hushed tones. Although scholars sometimes liken it to the guillotine or electric chair, such analogues do not do justice to the slow, emasculating death its victims underwent. To suggest that Jesus – a god – died this way? Sheer insanity.

My initial reading of the donkey’s head, then, was that it captures the folly of the cross - the donkey being a quintessentially foolish creature.3 It is a striking illustration of Saint Paul’s comment that the cross is foolishness to the Greeks.

Worshipping a Donkey

Upon further research, however, I noticed that it is not only Christians who were taunted as worshipping the head of a donkey. The accusation of onolatry – of donkey worship – had already been direct towards Jews before them.4

We see this in Josephus’ apologetic, Against Apion, in which the historian defends Judaism against the charge that it worships a donkey as god (2.112-114).

Apparently, the myth of Jewish onolatry was widespread, for Tacitus includes it in his own Histories: ‘In the innermost part of the Temple, they consecrated an image of the animal which had delivered them from their wandering and thirst’ (5.4.2).

The revelation of ‘onolatry’ had me rethinking the image. Was it the case that the graffiti artist knew that Jesus worshipped a human, who was being represented here as a donkey, or did the artist actually think that Christians were donkey-worshippers?

The suggestion that non-believers thought that Christians worshipped a donkey may sound unbelievable, but in the ancient world, non-Christians sometimes had only half-garbled impressions of what Christianity was about.

For example, In the second century, Christians had a meal called the agapé – a ‘love feast’ – in which they addressed each other as siblings, and were known to consume the Lord’s supper, the body and blood of Jesus. With such rumours, some pagans garnered the impression that Christians were engaged in incest.

Might the non-Christian graffiti artist have had a similar misconception of Christians as worshipping the head of a donkey? An inheritance from their Jewish roots?

No - we don’t worship a Donkey!

The charge that Christianity worshipped the head of a donkey was one which Christian apologists took seriously. Consider, for instance, Minucius Felix, an African apologist who counters this claim around the time of the Graffito:

‘Thence arises what you say that you hear, that an ass's head is esteemed among us a divine thing. Who is such a fool as to worship this? Who is so much more foolish as to believe that it is an object of worship? (Minucius Felix, Octavius, 28)

Like Tertullian before him, Minucius goes on to attribute the claim to Tacitus and subjects it to a devastating self-critique.5 As Tacitus later lets slip in his Histories, when the Romans entered the Temple, they found nothing of the sort. Tacitus doesn’t get his story straight.

In any case, Minucius asks, is it not pagans who worship gods in the form of animals - not Christians? As the Latin apologist asserts at length, Christianity was aniconic in its practice; it did not have statues and idols and altars like Roman religions.6 This can partially explain why some of the earliest images of Jesus were not explicitly Christian.

The Graffiti Today

We’ve looked through the Alexamenos as a window onto ancient Christianity. But does it bear any significance today, other than as an inconspicuous bit of culture?

Unfortunately, I was not able to find Alexamenos or his ‘god’ on my trip to Rome. But the sheer difficulty of finding the object was perhaps a lesson in itself.

It is hard to ignore the irony that the delicate etching is stored behind glass in a scaffolded museum - the burden of the scholar to dig out. Meanwhile, the city itself is awash with crosses - for Christians, the ultimate of God’s life-giving love.

The (anonymous) graffiti artist put the writing on the wall – worship God! – but it was the Roman Empire itself which responded, don’t mind if we do.

Now, the folly of the cross has been swallowed up in a city which embraced its power. But the graffiti seems more than ever like graffiti. A misguided protest from below.

Joan E. Taylor, What did Jesus Look Like? (London: T&T Clark, 2018), 105.

According to one expert, the Alexamenos Graffiti suggests that outsiders shared an awareness of “the significance of Jesus’ Crucifixion (at least in terms of it being a powerful and efficacious symbol); and secondly, a consciousness of the existence of Christian representations of the Crucifixion by the early 3rd century…” See Felicity Harley-McGowan, “The Constanza Carnelian and the Development of Crucifixion Iconography in Late Antiquity” in ‘Gems of Heaven’: Recent Research on Engraved Gemstones in Late Antiquity, c. AD 200-600, eds. Chris Entwistle and Noël Adams. British Museum Research Publication 117 (London: The Great British Museum), 214-220 (218).

On the mixed reception of donkeys in the ancient world, see Peter Mitchell, The Donkey in Human History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), e.g. 230.

On the variations of onolatry, and the suggestion that it emerged from the claim that God’s name is ho onos (‘the one who is’), which sounds similar to onos (donkey), see Jan M. Kozlowski, “God’s Name ὁ Ὤν (Exod 3:14) as a Source of Accusing Jews of Onolatry,” Journal for the Study of Judaism in the Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman Periods, 49 n.3 (2018): 350-355.

See Tertullian, Nat. 1.14; Apol. 16.1-13. Other apologists who treat the claim include Origen (Cels. 6.30) and Epiphanius (Pan. 1.28).

For a treatment of early Christian aniconism, see Robin Jensen, “Aniconism in the first centuries of Christianity,” Religion 47 n.3 (2017): 408-424.