Coins, Stones & Ossuaries

How Five Archaeological Finds Illuminate the Gospels

What can archaeology teach us about the Bible?

This is a question with the potential to make scholars wince. It conjures images of eccentric gentlemen in Indiana Jones-style dress on a quest to find, if not the Holy Grail, then the Kingdoms, chronologies and artefacts of the biblical histories.

When the field of biblical archaeology was founded in the 19th century, it was not quite this caricature, but it was also not far off. Looking back, the (unspoken) purpose of the field was to fill out and harmonise the textual traditions of the Bible. It was an archaeology in service of biblical literalism. An archaeology with apologetic aims.

Today, things look reasonably different. Since a paradigm shift in the 1970s, the field has not so much sought to ‘prove’ the Bible, as it has to understand the life and world of those who lived in and around ancient Palestine.1 Bearing a closer relationship with the social sciences, archaeologists re-construct life beyond and behind the texts, whether or not these confirm or contradict the record of the biblical stories.

With the spirit of this research in mind, I want to take a look at five archaeological finds which relate to the gospels. From the coinage of Herod Antipas to the latest research on first-century Nazareth, I examine how these incredible discoveries provide windows into the lives of Jesus, his family and earliest followers.

1. The Coins of Antipas

In a passage shared by Matthew and Luke, we find Jesus asking this question about John the Baptist:

What did you go out into the wilderness to look at? A reed shaken by the wind?25 What, then, did you go out to see? Someone dressed in soft robes? Look, those who put on fine clothing and live in luxury are in royal palaces. 26 What, then, did you go out to see? A prophet? Yes, I tell you, and more than a prophet.

Jesus here contrasts the greatness of John – known for his shaggy look – with those who live in luxury. Yet Jesus does not direct his criticism to any particular person.

Or does he?

When we take a closer look, this passage may contain a thinly veiled critique. In referring to a ‘reed shaken by the wind’, some scholars have imagined that Jesus had a particular person in mind: John’s arch-nemesis, the tetrarch Herod Antipas.

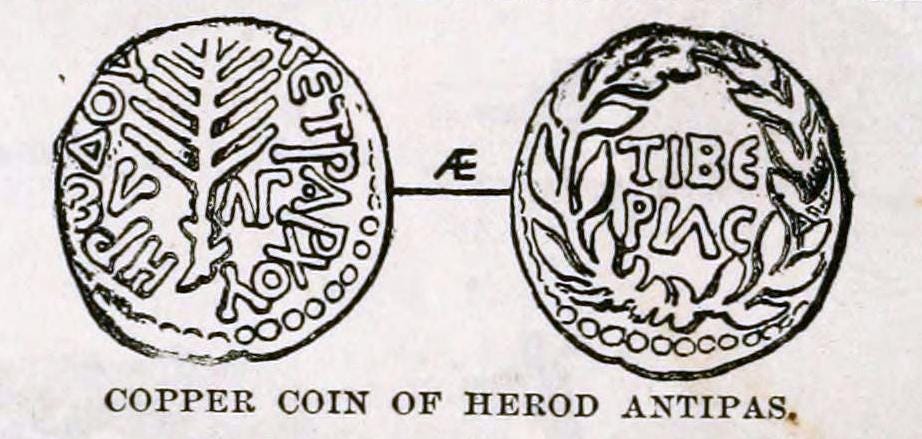

To see this connection, we need to appreciate the ancient coinage that Jesus and his contemporaries would have turned over. For the symbol Antipas imprinted on the coins he minted were palm reeds:2

If this association between Herod and reeds is true, then Jesus may be contrasting Herod with John. Herod is a ‘reed shaken by the wind’. By contrast, John was more than a prophet.

To be sure, the ‘reed’ image need not evoke a specific individual. It is used several times in the Bible to describe those without a strong moral backbone.3 Yet in the setting of this verse, a reed would be exactly the right metaphor to describe Antipas: he had broken Jewish law by divorcing his first wife and marrying his brother’s wife, and John the Baptist had been put to death for calling him out on this bad behaviour.

This veiled allusion may also betray a protective strategy on Jesus’ part. We know that Jesus took care to avoid the wrath of Herod – and here Jesus knew better than to call out Antipas by name. His strategy was to use the imagery of his coinage instead.

This is a reminder of how subtle communication can be. Jesus’ teaching did not take place in a vacuum. If we don’t explore his world, there will be clues we easily miss.

2. The Ossuary of Alexander

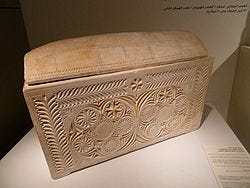

We move now from coins to bones and the boxes or ‘ossuaries’ that held them. From the first-century BCE, wealthy Jews would exhume the skeleton of a deceased family member into an ossuary after some time after their temporary burial.

Why exactly Jews began this practice is debated. Many scholars repeat the classic argument that it reflects Jewish beliefs about resurrection. Similar to a ‘Christian’ burial, the interment of the skeleton would allow God to re-flesh the skeleton’s bones.

Yet not only is it unclear how many first-century Jews believed in a bodily resurrection, we have the ossuaries of Sadducees who certainly did not believe in it. It may be, then, that practical rather than ideological factors such as the wealth of Jerusalem and the rise of stone-masonry lie behind the practice.4

For our purposes, what is remarkable is that numerous ossuaries were named. This means that we appear to have some of the ossuaries of people who appear in the gospels, including the High Priest Caiaphas, who presided over Jesus’ death.

Yet in my view, this is not the most fascinating ossuary to survive. Another bone-box bears the name ‘Alexander (son of) Simon’ in Greek, while on its lid is etched the Hebrew ‘Alexander the Cyrenian [קרנית].’5 Who was this Alexander, Son of Simon?

The Gospel of Mark may hold an answer. In Jesus’ journey to Golgotha, a certain ‘Simon of Cyrene’ is enlisted to help him carry the cross. While it is not usual to disambiguate a name by a person’s father, we are told that this Simon himself was ‘the father of Alexander and Rufus.’ Why mention Simon’s own children? Apparently, this pair – Alexander and Rufus – were known to Mark’s audience.

Could this ossuary contain the bones of the Alexander referenced in passing by Mark?

Before we get ahead of ourselves, Alexander and Simon were common names in antiquity. Yet this is the only ossuary with the name 'Alexander (son of) Simon’, and the reference to Cyrene adds a further level of specificity. It is therefore not surprising that several scholars, including some highly critical of the reliability of the Gospel tradition, have suggested that we do have the bone-box of Mark’s Alexander.

It is fascinating to speculate on who this Alexander and his father, Simon, might have been. Did they convert to the Jesus movement, or were they already part of it? Did Alexander’s own testimony lie behind this part of Mark’s passion narrative?

While it is difficult to come to firm answers, it seems he was known – in person or reputation – to Mark’s audience, but perhaps not to the later evangelists, who cut him out. The bone-box of Alexander thus gives us a glimpse into the life of Jesus’ early followers: lives steeped in Jewish custom and ritual, whatever their newfound beliefs.

3. Yehohanan’s Heel

What was crucifixion like for Jews living in Palestine? Excerpts from literary texts tell us part of the story. But for a long time, archaeology had virtually no material to work with to inform our understanding of the Roman practice in Judea.

This all changed in 1968, when the skeletal remains of a man named Yehohanan (Jonathan) were found in an ossuary.6 Remarkably, Jonathan’s heel-bone had been pierced with an iron spike, 11.5 cm long. It looks like Jonathan was a victim of crucifixion, sometime in the late 20s CE, under the reign of Pontius Pilate.

There are two reasons why this finding may be significant. The first is that it is hard evidence that Jewish victims of crucifixion did at least sometimes receive a burial. This runs against the view that crucifixion victims were refused burial and Jesus’ corpse would have been left to rot on the cross.

To be sure: we might think that Jonathan’s remains were the exception. Yet the very fact that we know that this particular Jonathan was crucified was itself only by chance because the nail bent back on itself. If others were crucified and such marks of crucifixion were removed, we would never know that they were crucified.

It is also important to recognise that the vast majority of first-century Jewish victims were crucified during the first Jewish war (c. 66-70) and were not granted burial. The vast majority were also poor, and therefore their bones were not preserved. It is thus difficult to see, on archaeological grounds alone, how exceptional Jonathan was.

At the same time, we must not make the false leap that because Jonathan was buried, Jesus must have been too. We do not know the reasons why Jonathan was crucified, or even how, why or when his bones were acquired. Our ignorance on these points makes it somewhat difficult to draw too strong an analogy to Jesus.7

Yet there is another reason why Jonathan’s bones are significant: they give us a picture of how a Jewish man may be crucified. Rather than only tied up with rope (see Pliny Sr. Natural History, 28.4), Jonathan’s bones show us that sometimes a spike would be driven through the heel. Interestingly, however, there is no evidence that Jonathan’s hands or wrists were nailed.8 The same may have obtained in Jesus’ death.

4. The Pilate Stone

Our fourth archaeological find was discovered in 1961 by a team from Italy who were excavating in Caesarea Maritima. This was the Palestinian sea-port city city significantly enlarged in the many building projects of King Herod the Great.

When they were excavating the theatre, they chanced upon a lime-stone slab, which had been re-purposed as a staircase. The broken text on the lime-stone read:

………STIBERIEVM

………NTIVS PILATVS

………………ECTVSIVDAE

…………….. ………………………

What exactly a ‘Tiberium’ was is difficult to say. It may have been a Roman Temple. What is clearer is that the second line refers to a certain ‘(Po)ntius Pilatus’, while the third provides his official title: ‘(Pra)ectus Iudae’ (Prefect of Judea). It therefore provides our first archaeological evidence for Pilate’s governorship of Judaea.9

If you plug the ‘Pilate Stone’ into google, you will find many books claiming that the inscription confirms and corroborates the historical reliability of the gospels. Yet for historians, the value of the Pilate Stone does not lie in confirming Pilate’s existence – a datum already known through clear literary evidence – but for illuminating his role.

Most importantly, the stone identifies Pilate as the Prefect of Judaea. This itself is a window into Jesus’ world, as Prefect was a military position. It tells us that the very purpose of Pilate’s role was to bring Judea under Roman military subjugation – a role that Pilate would express in suppressing (alleged) kingly figures like Jesus.

When we turn to the textual evidence, the terminology of Pilate’s role is unclear. Philo, Josephus, and the New Testament call various governors hegemōn (‘governor’), eparchos (‘prefect’), and epitropos (‘procurator’). The overlap may reflect the change from Prefect to Procurator under Claudius, when the title’s terminology shifted from a military role to a financial one – a move perhaps designed to reflect the success of Rome’s military subjection. The Pilate Stone clears up any literary confusion.

5. First-Century Nazareth

When archaeologist Ken Dark turned up to Nazareth in 2006, it was to study the town as a centre of Byzantine pilgrimage. Yet his attention quickly turned to antiquity when he unearthed a first-century home beneath a seventh-century Church.

Dark thinks that this dwelling may be Mary’s home. Yet even if we are not sure about this, Dark’s fourteen-year excavation of Nazareth has yielded a number of results about the socio-religious conditions of the town. Here I draw attention to just one result: the material culture of Nazareth and its nearby town, Sepphoris.

Sepphoris is just four miles from Nazareth. It might be expected then that it forged promising links with Jesus’ hometown. In relation to Jesus’ missing years, scholars have often supposed that Jesus might have found work there. It is supposed that Jesus may have even played a hand in the construction of its Greek theatre.

Yet Dark’s portrait tells a very different of these two towns. In Nazareth, limestone vessels were used to avoid ritual purity, while the material culture of Sepphoris is more varied, revealing imports from non-Jewish communities. For Dark, Jesus’ Nazareth was “exclusively Jewish” with a special concern for ritual purity.10 It was actively resisting the Roman provincial culture which Sepphoris had embraced.

Dark goes so far to say that there “was probably little or no contact between first-century Nazareth and Sepphoris, despite their proximity, due to the deliberate choice on the part of the people at Nazareth to keep themselves separate from Sepphoris”11 He supports this view by pointing to the independence of their economies.

To hear that Nazareth was a deeply pious town, perhaps even in active resistance to Roman culture, makes a good deal of sense. Jesus seems to have directed his mission to ‘the lost sheep of Israel’ (Mt. 15:24), while the major ‘Greek’ cities are never mentioned in the Gospels. If Jesus was raised in a small town which resisted Roman life, we can begin to imagine the crucible in which his sense of religiosity emerged.

Why does Archaeology Matter?

When it comes to reading the gospels, archaeology matters. But not simply for the purpose of corroborating the biblical record. At times, we find gospel figures appearing in our material sources (Pilate, Alexander, Caiaphas). Yet the most unique insights of archaeology lie in how they illuminate the world of Jesus and his followers.

Turning over a coin can tell us how Jesus’ words can be read. Looking at the skeletal remains of a crucifixion victim can tell us what ancient crucifixion was really like. Pulling back a theatre staircase can reveal the nature of Pilate’s role. And the excavations of Nazareth gives us a glimpse into Jesus’ childhood and young adult life.

In all of these ways and more, archaeologists expose the brutal life of first-century Palestine: a life in which Jews made attempts to follow their own laws and customs against Hellenistic impingements, launched veiled critiques of Roman hegemony, and sometimes paid the ultimate price for doing so. As archaeologists peel back the layers of first-century Palestine, they take us even further behind the Gospels.

On this turn in ‘biblical archaeology’, see William G. Dever, What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It? (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2001); Thomas W. Davis, Shifting Sands: The Rise and Fall of Biblical Archaeology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

See Gerd Thiessen, ‘Das “schwankende Rohr” in Matt. 11,7 und die Gründungsmünzen von Tiberias. Ein Beitrag zur Lokalkoloritforschung in den synoptischen Evangelien’, ZDVP 101 (1985): 43–55; cf. Jean-Philippe Fontanille, Aaron Kogon, Jean-Philippe Fontanille, The Coinage of Herod Antipas: A Study and Die Classification of the Earliest Coins of Galilee (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 17, 45–6.

See 1 Kgs. 14:15; 2 Kgs. 18:21; Ezek. 26:9-7.

See Steven Fine, “A Note on Ossuary Burial and the Resurrection of the Dead in First-Century Jerusalem,” Journal of Jewish Studies 51 n.1 (Spring 2001): 69-76.

There is some doubt as to what exactly קרנית means. It is variously translated as ‘the Cyreneaite', ‘the Cyrenian’ or as otherwise referring to Cyrene. Yet doubts as to the exact translation are mitigated by the fact that adjacent ossuaries have names more typical of Cyrene than Jerusalem. See Craig A. Evans, Jesus and the Ossuaries: What Jewish Burial Practices Reveal about the Beginning of Christianity (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2003), 94-96.

Here I follow Craig A. Evans, “Jewish Burial Traditions and the Resurrection of Jesus,” JSHJ 3 n.2 (2005): 242-43.

See Bart D. Ehrman, "The Skeletal Remains of Yehohanan and Their Significance,” July 31 2014 (Bart Ehrman Blog) [Accessed Friday 19th September 2025]

Other literary sources indicate that sometimes a person’s hands or wrists were nailed. See the anonymous third-century, Apotelesmatica 4.198-200. Evans, “Jewish Burial Traditions,” 243.

For the following discussion, see Helen K. Bond, Pontius Pilate in History and Interpretation. SNTSMS 100 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 11-12.

Ken Dark, Archaeology of Jesus’ Nazareth (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023), 161.

Ibid. 161.