How Classical Art Gets the Gospels Wrong

Seven Famous Artworks which Misrepresent the Gospels

To enter a Western art gallery today often feels like stumbling into an alternate Universe. A world in which Christian iconography confronts your vision at every turn. A past in which the gospels were not so much read as they were seen.

It is also (in my case) to enter a space which opens up fields of study I am never quite sure what to do with. I really wish I could explicate the philosophical choices beneath the thicker brushstrokes in this piece and the realism (?) of the Chiaroscuro (??) in that.

But I am not an artist. Nor an art historian. My training is in biblical studies. Perhaps inevitably then, my focus turns elsewhere: to the biblical scenes themselves. Or more precisely: to the relationship between the artworks and the episodes they represent.

It is that relationship which I want to touch on in this piece. If classical art is a window into how people once read and still read the Gospels, what are some of the ways we have grown used to ‘reading’ the Gospels which are not so true to the text?

Here I look at seven famous and more-or-less ‘classical’ artworks which still inform our idea of the Gospels – and examine how classical artists got the Gospels wrong.

1. Da Vinci, The Last Supper

Da Vinci’s classic mural presents its viewers with a peculiar Last Supper, but not only for the reason it is often parodied (‘can we get a table for twenty-six please?’)

Most unusual about this depiction it makes no effort to resemble the Passover. Here the meal takes place during the day (Passover was at night); it features fish and leavened bread (lamb and unleavened bread were consumed in the feast); while the Twelve sit on chairs (the ancient tradition hints the custom was to recline.)

Da Vinci’s Last Supper might also take the blame for the popular idea that Jesus’ shared his final meal with ‘The Twelve’. Reading the Gospels, this was not the case. Passover was a wider family affair. The fact that Jesus orders a ‘large room’ and has to clarify that his betrayer was among the Twelve only confirms this impression.

2. Girolamo da Santacroce, The Adoration of the Three Kings

Santacroce’s stunning variation of the Adoration-motif portrays three Kings paying homage to the infant Jesus. The scene derives from Matthew’s birth narrative. Yet a closer reading reveals that the three kings are completely absent from the text.

In Matthew, Jesus is visited by an unspecified number of magoi. This is the word from which we derive ‘magician’ – a common pejorative in antiquity. Here, however, there is nothing negative about the magi. Some scholars therefore think they refer to the revered priests of the Persian court, who also pop up in stories of Alexander’s birth.

Why then does Santacroce present the magi as three Kings? The number three is popular in Western tradition, presumably as a result of the three gifts the magi bring (gold, frankincense and myrrh). Yet the idea of ‘three’ kings was by no means fixed early on. Even today in Eastern tradition, they magi are as many as twelve.

As for the notion that they were Kings, the Christian writer Tertullian had already described the magi as ‘wellnigh kings’ (fere reges) in the second century.2 Yet he has derived this imagery from the gift-giving of kings in Psalm 72. In Matthew’s text, the only Kings in sight are Herod the Great and his still greater Messianic contestant.

3. Titian, The Penitent Magdalene

Titian’s penitent Magdalene shows Jesus’ disciple, Mary, in a sensual pose. Her rosey cheeks, exposed skin and long-flowing hair allude to her sinful life as a prostitute.

Yet as with the three kings, there is a problem: the gospels never actually describe Mary as a prostitute. This long-standing tradition lacks any basis in literary or historical fact. In the gospels, Mary is simply described as one of Jesus’ followers who had ‘seven demons’ cast out of her (Lk. 8:2). She is never once associated with prostitution.

How then did Mary become the prostitute of Christian tradition? This association can be traced to a homily by Pope Gregory in the late sixth-century. To arrive at the view, the Pope was conflating three different women: Mary Magdalene, Mary of Bethany (John 11) and the unnamed ‘sinful woman’ who anoints Jesus’ feet in Luke 7:36-50.

Yet these are clearly not the same Mary. The two Mary’s are identified with two completely different locations: Magdala was a fishing town in Galilee; Bethany was a town close to Jerusalem. Moreover, the scene in Luke 7 has some very different features to Mary of Bethany’s anointing of Jesus. It does not prepare him for burial.

Sadly, the idea that Mary was a reformed sinner has often clouded her importance in the Christian tradition as the first witness to the resurrection and the Apostola Apostalorum (‘the apostle to the apostles’). Since 1969, the readings on her Saint’s day in the calendar of the Catholic Church have been altered to reflect this fact.

4. Caravaggio, The Incredulity of Saint Thomas

We all know John’s story of Doubting Thomas, immortalised in Caravaggio’s masterpiece. Unlike the other (less doubtful disciples), Thomas will not believe in the resurrection until he puts his hands in Jesus’ side. So he proceeds to do just that.

This version of the story is so well-known that it is baffling to learn that John never narrates it – or at the least, not explicitly. In the text, a traumatised Thomas claims that he will not believe until he sees and puts his ‘finger in the mark of the nails and my hand in his side’ (20:25). Jesus then commands him to do so.

Yet John never describes Thomas putting his fingers into Jesus’ marks. Upon seeing and hearing the command of the risen Jesus, Thomas simply proclaims: ‘My Lord and my God’. For Thomas, it seems to have sufficed that Jesus acknowledge his earlier turmoil. To see the risen Jesus might have been enough for him, after all.

Of course, it is quite possible that the reader is left to infer that Thomas did indeed touch Jesus’ wounds, as Caravaggio depicts. Yet if this is the case, it somewhat tempers the point of the story. For as Jesus says to Thomas: ‘because you have seen me, you believed; blessed are those who have not seen but have believed’ (20:29).

5. Sir John Everett Millais, Christ in the House of His Parents

This Victorian painting is a variant of the popular motif of Jesus in his father’s workshop. It visualises the gospels’ portrayal of Jesus and his dad as carpenters.

The difficulty with this depiction is that the Greek term tektōn does not necessarily refer to a ‘carpenter’. As historians of Jesus have long pointed out, a tektōn was anyone who worked with hard materials – this could include wood, but also with stone.

Given this wider scope, historians have suggested that a better term might be a ‘craftsman’, ‘handy man’ or ‘builder’, reflecting the range of skills a Galilean peasant might have required. This latter suggestion is supported by an ancient text, the Protoevangelium of James, which imagines Joseph as a ‘builder of buildings’ (9).

The idea that Jesus was a carpenter has a long history. The Infancy Gospel of Thomas imagines Jesus helping his father by shortening and lengthening pieces of wood. One sixth-century text is The History of Joseph the Carpenter. Yet if scholars are right, the trade-skills in Jesus’ oeuvre may have been wider than history has often imagined.

6. Limbourg Brothers, Nativity (folio 44, verso)

There is something especially strange about this fourteenth-century miniature.

Have you spotted it?… Yes, Joseph is wearing a Turban!

Which raises the question: did ancient Jews wear turbans? The answer is that they did not. As Ivan Kalmar has shown in his excellent piece, “Jesus Did Not Wear a Turban”, the idea of Jews wearing turbans is part of an “Orientalising” of the Jews which may stretch back as far as the Twelfth Century. Medieval art depicted Jews as Muslims.

This development occurred for historical and theological reasons. Historically, the Ottoman Empire made gains in Constantinople and the Holy Land. It thus became possible for Western Christians to imagine and clothe their idea of biblical history in contemporary Muslim aesthetics. To think of ‘the East’ was to think of Islam.

Yet theologically, it is remarkable that Jesus and his disciples are only rarely depicted in the same attire. This reflects the belief that Jesus and his disciples had somehow surpassed – or superseded – their ‘Eastern’ environment. The Jewish Pharisees have have looked like Muslims, adorned with their turbans – but Jesus certainly did not.

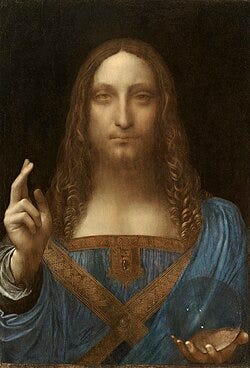

7. Da Vinci, Salvator Mundi

Finally, we return to the master – Leonardo – and the biggest anachronism in classical depictions of Jesus: the fact that they rarely resemble a first-century Galilean Jew!

To be sure, this anachronism is not uncommon in religious art. Nor is there anything particularly wrong about European artists imagining Jesus as someone like them – insofar as they are not depicting Jesus as he actually looked.

The problem is that many European artists did believe Jesus looked like this. This error can be accredited in part to the popular medieval forgery, The Letter of Lentulus, which posed as a first-century description of Jesus’ physical appearance. The letter casts Jesus with the very Caucasian features we find in Da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi, including his long-flowing curly hair parted in the middle – the colour of an ‘unripe hazelnut.’

It almost goes without saying that ancient Jews did not look like this. Those who want to know more about what Jesus’ appearance can now consult Joan Taylor’s brilliant monograph, What did Jesus Look Like? (2018). On the question of Jesus’ hair, Taylor notes the fashion of the time was to wear it a short. (A ‘long-haired’ Jesus would come along only later, when Christians cast Jesus as a philosopher and a god.)

Re-Imaging the Gospels Today

From Orientalising turbans to a carpenter’s workshop, classical art teaches us how easy it is to read in and out of the Gospels what was never there. How centuries of tradition overlay the gospel texts – often obscuring their original meanings.

Some of these distortions may be quite harmless. To imagine Jesus as a ‘carpenter’ may be to miss out on some of what Jesus got up to in his young life, but it is not to seriously distort the meaning of his text. Yet other depictions are less innocuous.

Perhaps the saddest effect of much classical art is to obscure Jesus’ first-century Jewish identity. Whether it is de-feasting his Synoptic last supper, contrasting him to (Orientalised) Pharisees, or casting him as a Caucasian, these details conspire to strip Jesus of his Jewishness and package him as the product of Western Christianity.

If there is one takeaway from this piece, it is perhaps related to this. Religious artists today – working in tandem with biblical scholars – can help to break the anti-Jewish, Eurocentric focus of classical art. In recovering the Jewish Jesus of the first-century, modern religious art might help us see even further behind the Gospels.

Further Reading

Joan Taylor, What did Jesus Look Like? London: T&T Clark, 2018.

Ivan Davidson Kalmar, “Jesus Did Not Wear a Turban: Orientalism, The Jews, and Christian Art” in Orientalism and the Jews, eds. Ivan Davidson Kalmar, Derek J. Penslar (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England), 3-31.

Very interesting! It has always frustrated me how Mary Magdalane's legacy has been tainted (as either being a whore or Jesus' secret wife- the two classic tropes for women I suppose).

P.s. I thought the brothers Limburg painted late 14th / early 15th century or is this a different miniature...?

What a wonderful subject and post! I submit for honorable mention the fifteenth-century Merode Altarpiece, sometimes called "The Virgin and the Mousetrap." It is a feast for the eyes, not to mention a banquet of Dutch anachronisms as its colloquial title suggests.