Christ the Construction Worker?

Taking a closer look at Jesus' profession

It is often thought that before his ministry, Christ was a carpenter.

We gain this impression from the Gospel of Mark, in which Jesus’ neighbours ask: ‘Is this not the carpenter [tektōn], the Son of Mary?’ (6:3). In Matthew’s Gospel, Jesus is called ‘the son of the carpenter,’ attributing the same profession to Joseph (13:55).

For the classical masters, these biblical passages provided inspiration for the image of the boy Jesus in his father’s workshop. We might think of Simone Barabino’s Christ in the Carpenter’s Shop (c. 1600), in which Mary looks lovingly over Jesus’ labour:

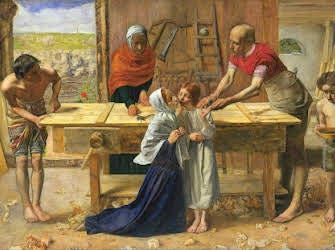

Or perhaps John Everett Millais’s Christ in the House of his Parents (1849-50), in which Joseph is hard at work on the sidelines, while Mary sweetly kisses Jesus’ cheek:

The image of Jesus in his father’s workshop is not, however, the preserve of classical art. Already in the late second century Infancy Gospel of Thomas, Jesus appears to have been rather handy to have had around. When his father cuts a piece of wood too short, Jesus exerts his miraculous powers to increase its length (8.1).

The idea that Joseph was a carpenter – as one of the few things known about him – has also been central to his memory. One sixth-century text, also concerned with Jesus’ childhood, is entitled The History of Joseph the Carpenter. Even today, in the Catholic tradition, Joseph is the Patron Saint of workers – especially carpenters.